introduction

Statement of Purpose:

There are more thangkas on view at tibetart.com than there are

presently on display in all the museums in the western world. Most of

the thangkas remaining in the world are now outside Tibet. The

majority reside in private or museum collections where many are kept

in storage, unavailable for study or enjoyment. This website seeks to

turn this tide of exclusion by opening its virtual halls to all.

tibetart.com will make thangkas available to scholars, lay people

and religious practitioners. When fully developed, tibetart.com will

provide scholarly forums and guided tours in addition to the

opportunity to search an extensive database of thousands of thangkas

dispersed around the world. In addition, the web site will contain

information and commentary on the historical and religious

significance of the thangkas and the iconographic and aesthetic

traditions which gave birth to them. New descriptions are being added

weekly by scholars internationally.

We extend an invitation to all collectors of Himalayan thangkas both

private and institutional to display your images at tibetart.com.

Through our combined efforts a culture in Diaspora can be preserved

and these beautiful and profound art objects made available to a

broader audience than has ever been possible before.

We invite your suggestions in response to the site. Email:

info@tibetart.com.

Origins of Tibetan Art

Tibetan Art can only be understood in the context of its sacred

Buddhist origins. The ancient King Srong Tsen Gampo unified the

then non-Buddhist country we now know as Tibet in the 7th century.

Establishing one of the largest empires in the history of mankind,

his domain stretched from Afghanistan to Xian, the capital of

China. King Srong demanded wives from the courts of his closest

neighbors, the Buddhist kingdoms of China and Nepal. It is the works of art that these two princesses brought with

them to Tibet that form the sacred seeds of the origins of Tibetan

art. The Chinese princess Wen Ju brought a pair of ancient life-size

sandalwood Indian statues of the Buddha said to have been made

as portraits during the lifetime of Shakyamuni Buddha. This statue was brought as an offering by Srong tsen gampo's Nepalese

wife, the Nepalese princess Brikuti. From these origins Buddhism

was established firmly over the next hundred years culminating

when the King Tri Srong De Tsen in the 8th century attempted to

lay the foundation for the first monumental temple and monastery

in Tibet at Samye. Local spirits were disturbed by these religious activities and

the greatest tantric Buddhist adept in India, Guru Rinpoche Padmasambava

was invited by the king to subjugate these spirits. Guru Rinpoche in many manifestations was completely successful

not only taming the local spirits but converting them to the protectors

of Buddhism in Tibet as well. Padmasambava was predicted by Buddha

Shakyamuni, and he taught the highest innermost Vajrayana Buddhist

teachings to the King and other Tibetan students. Little remains of this early period when Buddhism and the building

of temples and the attendant art and artifacts prospered for nearly

a hundred years. Mid-way through the 9th century the despot Langdarma

murdered his elder brother the Buddhist king Rapalcen and usurped

the throne in an anti-Buddhist campaign. Then Buddhism and its

artistic forms were violently purged. In a cultural brain wishing

campaign not unlike the violent purges of Buddhist antiquities

during the Chinese Cultural Revolution of the 1960's and 70's

in Tibet when 6000 monasteries were destroyed and sacred bronze

and painted images were desecrated, the despot Langdarma destroyed

any artistic expressions of monastic or public Buddhism in any

form. After a brief and destructive reign he was assassinated

by the Buddhist monk Lha Lung Pelki Dorje. At this point the centralized

empire of Tibet fell back into disparate feudal states breaking

up into small often warring enclaves. A dark age ensued for over

150 years. Then, in a small kingdom in Western Tibet (Tib: Ngari),

under the kingship of Yeshe O, Buddhism and its attendant art

forms of architecture, sculpture, and painting were totally revived.

King Yeshe O had sent 21 promising young monks in 950 to study

in the monastic Collages in India with the aim for them to return

to their homeland to establish centers of buddhist learning. The

tropical climate killed all but two monks, one Rinchen Zangpo

completed his studies and returned with a band of Indian master

artists decades later. Living well past the age of 100 he established

at least 21 temples and translation centers in Western Tibet.

What we see remaining of these temples frescoes, some of which

are now preserved in temples in the Indian Himalayas, reflects

the fluorescing of Indian, particularly Kashmiri Buddhist art

before dying out completely under wave after wave of Moslem invasions

(not one painting on cloth of this period remains in India!).

Along with paintings and statues of Buddhas which take many forms,

both human and fantastic and male and female we find surviving

frescoes of mandalas. Mandala paintings are two dimensional representations of the multidimensional

universes these Buddhas inhabit. Mandalas are not to be understood

as representing someplace different from where we are right now

. Rather mandalas display an Enlightened ever present world that

is revealed when the dualities of anger, attachment and ignorance

are stripped away. Actually these enlightened worlds are constructed

of these very same energies that in our dualistic view we perceive

as anger, attachment and ignorance but in the unencumbered enlightened

state these same defiled emotions manifest as strength, compassion

and wisdom. In this sense mandalas are much like architectural

blueprints or aerial views of celestial palaces constructed of

enlightened concepts. For example, mandalas are usually laid out

on a compass like grid; the western quadrant appears red representing

the transmutation of desire into discriminating wisdom. The surviving frescoes of mandalas of these mediation cycles (sanskrit:

tantras) that were translated and transmitted by Rinchen Zangpo

in Western Tibet convey the vivid confidence the artists at the

time had in Buddhist practice. The almost erie use of chiaroscuro

conveys a palpable mystical presence to the deities and their

enlightened settings. These Buddha's are shown clothed in silks

who designs give us a distinct time frame to date the paintings.

Over the centuries Buddhism took hold throughout Tibet. The artistic

traditions of India and later the styles of Nepal and eventually

China influenced Tibetan art. Exquisite Buddha images were caste

using alloys whose production was of alchemical proportions. Even

today Tibetan bronzes of the early period display inexplicably

beautiful patinas. Tibetan culture is at a crossroads now. We are left to sort through

the few remnants of Tibetan art history left over from the treasure

trove that was destroyed during the Chinese Cultural

Revolution in Tibet. As the scholar David Jackson has said "One of the

most serious problems facing historians of Tibetan art is the fact that

the sacred artworks have been since the 1960s uprooted and scattered far and

wide. Although many paintings were originally parts of multi-thangka sets, now

they often hang alone somewhere in the West as single paintings... One basic

task of the researcher is to try to discover the lost order in this chaos..."

Through the participation of private and public collections world wide

in tibetart.com we can reassemble if not physically than at least

virtually the remaining artworks and give access to people all

over the world to the knowledge and aesthetics of one of the last

surviving ancient wisdom traditions.

The Himalayan Art Project

of the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation

has as its goal to preserve the sacred Buddhist art of the

Himalayas.This art emanates from the sacred traditions around which

the profound and ancient cultures of Tibet and its neighbors have

flourished over the last thousand years.

- Moke Mokotoff

- Moke Mokotoff 2/98

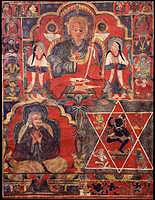

The 7th Century king of Tibet, Srong Tsen Gampo and his two Queens

Buddha Shakyamuni

The most highly venerated and important work of art, the Jo rinpoche

now enshrined in the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa is one of these.

This statue was the most common object of pilgrimage whereby 100s

of thousands of Tibetans over the centuries walked and sometimes

prostrated thousands of miles to venerate this icon. The next

most important image in Tibet was the sandalwood image of Avalokiteshvara,

the patron bodhisattva of the land of snows. The mantra of Avalokiteshvara is Om Mani Padme Hum.

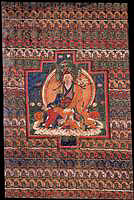

The 8th century king, Tri Srong Detsen invited Padmasambava to

Tibet

Guru Rinpoche took many manifestations in Tibet

![]()

Readily available books:

Mystic Art of Ancient Tibet

Blanche Olschak and Geshe Thupten Wangyal, Mc Graw - Hill, 1973Tibet a Lost World

Valerie Reynolds, Newark Museum, 1978Tibetan Art

P. Pal, LA County Museum 1988Tibetan Thangka Painting

David and Janice Jackson, ill. by Robert Beer, Serindia London 1984Wisdom and Compassion

Robert Thurman and Marilyn Rhie, Abrams